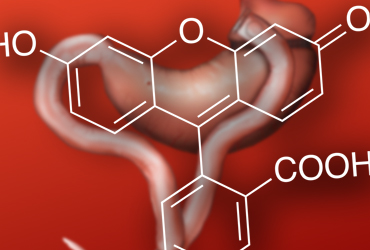

Agree. Fluorescence imaging provides surgeons with a new perspective on intraoperative anatomy by allowing them to operate outside the white light visible spectrum. While other surgical disciplines have been using this technology for some time, it has been popularized in colorectal surgery using a dye called indocyanine green (ICG), which shows bowel and anastomotic perfusion when given intravenously.

The main determinant of a successful anastomosis is the blood supply, and if using ICG—one can more objectively assess this than with more traditional and subjective techniques like cutting the nearby mesentery and waiting for a spurt of blood—then it seems like a sensible thing to do. Although randomized controlled trials are still in progress (InTact in the United Kingdom), the current phase 2 evidence from the PILLAR II trial (J Am Coll Surg 2015;220[1]:82-91.e1) and European equivalents shows that leak rates are reduced to less than 2% when using ICG to assess the anastomosis. In these reports, there have been cases where the resection margins have been changed based on the ICG assessment. Fluorescence imaging will be used more widely throughout surgery, and its utility for assessment of bowel perfusion seems particularly useful.

Disagree. Fluorescence imaging hypothetically ensures adequate perfusion to a new anastomosis, but there aren’t any high-level data to support the hypothesis. It may be helpful for selected patients where perfusion is uncertain, but I’m not sure one could support routine use at this time. With so many patient factors and technical factors affecting leak rate, it’s difficult to determine what percentage of the variability in anastomotic leaks is truly determined by such a test.

In the PILLAR II trial, fluorescence angiography changed surgical plans in 8% of patients, but there’s really no way of knowing if this altered surgical plan actually affected leak rates, especially considering that the cohort’s overall leak rate was only 1.4%. I was hopeful that the PILLAR III randomized controlled trial would answer this question, but it was unfortunately closed prematurely due to poor patient accrual.

On the fence, but mostly agree. Anastomotic leaks are one of the most feared complications of colorectal surgery. To date, there has not been a definitive method of preventing this complication, even when every basic tenet of surgery is applied during the making of an anastomosis. The uses of intraoperative Doppler and fluorescein have been the poor man’s tools to evaluate blood flow, but that has not correlated with end organ oxygenation and subsequent healing.

Fluorescence imaging is a great idea in theory as it evaluates the blood flow in the microvasculature. There is significant evidence that the use of fluorescence imaging is effective for identifying varying degrees of blood flow in the bowel. Confirmation of adequate bowel vascularization has been shown to decrease the rates of anastomotic leaks significantly. However, even with confirmation of blood flow using fluorescence imaging, there remain patients who experience anastomotic leaks, and full prevention of leaks has yet to be achieved. Thus, there appear to be factors that affect anastomotic healing, such as the bowel microbiome and various inflammatory mediators that have yet to be defined. In short, the available fluorescence imaging technology has been demonstrated to be effective at evaluating blood flow to anastomoses and should be routinely included in the evaluation of a newly constructed anastomosis to lessen the possibility of an anastomotic leak.

Please log in to post a comment