“It can’t happen to us” just happened. What do you do when your hospital faces sudden closure because it has defaulted on its loan from private equity? What do you tell your patients when their surgery, scheduled weeks before and with the appropriate prior authorizations, is canceled because the equipment vendor refuses to restock supplies until the bill is paid? What do you say to the OR nurses and techs when they ask you if they should find another place to work? We are trained to handle emergencies under extreme circumstances, but I don’t believe we are prepared for what is happening in healthcare today. Perhaps it’s time to figure it out.

To begin, we have to look back at how it all started. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was modeled after Romneycare, a business model designed with private equity in mind. Invest in a distressed industry with guaranteed government revenue, plow (borrowed) money into it under the guise of improved services, transfer the debt, and then sell it off for its parts. And because healthcare is a necessity, bailout is guaranteed. Non-profits and profits alike used the same playbook. The only problem is it was all put on the backs of taxpayers, and now the money is running out.

The moment the ACA was inked, you may recall, the cost of everything went up. We had to throw away perfectly good equipment; expiration dates changed; we were prohibited from reusing anything; and, of course, pain pumps became protocol. The term “evidence-based medicine” became a euphemism for paid for by insurance. The middlemen—the group purchasing organizations and pharmacy benefit managers—had a field day setting prices. And why not? The government and subsidized employer-based plans were footing the bill. Why not charge what you want?

As surgeons, we started off as involuntary participants in this system, but eventually gave in because arguing about the utility of replacing your prep solution from a traditional antiseptic that cost one cent, to a flammable solution in a nonrecyclable plastic container at 400 times the price wasn’t worth the risk for a sham peer review. We surgeons became enablers mostly because we couldn’t afford to complain.

But the system started to unravel when health insurers began shifting the burden of cost directly onto the patients. Services were covered and approved by insurance but now subject to a deductible. Even a trauma activation at a Level III center is an allowable charge, but it ends up being the patient’s responsibility. Paying premiums, taxes and deductibles was no longer affordable. Not only did this affect low-wage employees disproportionately, it rapidly increased the outstanding AR for hospitals and doctors (www.axios.com/2024/ 01/ 17/ health-insurance-premiums-wages). It’s not just about Medicare and Medicaid cuts; it’s about losing major revenue from Blue Cross patients who don’t, or can’t, pay the deductible or co-insurance. And because hospital CEOs live for volume, no one paid attention; as long as the OR was booked or the beds were filled, business was good.

Except it wasn’t. Medical debt is now the No. 1 reason for bankruptcy. It doesn’t matter how many RVUs you generate if no one pays the bill. Those left in private practice saw this coming, and it’s why there are so few of us left.

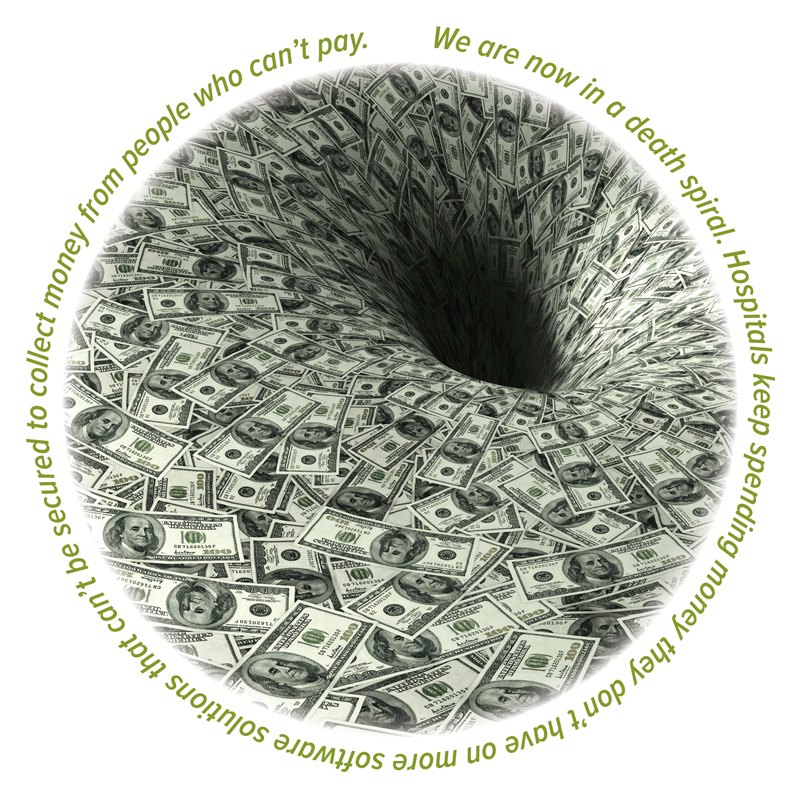

We are now in a death spiral. Hospitals keep spending money they don’t have on more software solutions that can’t be secured to collect money from people who can’t pay. My hospital and the private equity company who owns it is the first in the state, but won’t be the last. Every hospital system is ready to collapse like a house of cards, and when it happens, we will ask why. But it was set up this way from the start. Pump money into healthcare, prohibit physician ownership but allow private equity, and the profits go to pensions and endowments rather than be reinvested in the local healthcare community served. Hard to believe healthcare is now the No. 1 industry in 48 out of 50 states, yet we have limited access and a shortage of doctors and nurses (www.healthaffairs.org/do/ 10.1377/ forefront.20220524.257311).

What to do? First, acknowledge we are part of the problem so we can be part of the solution. We need to take on more fiscal responsibility for our patients by better understanding the cost to them. It’s important for our residents as well to know when they order another test or open a piece of equipment, what the price of that test or equipment is. And if it sounds absurd, question it.

Maybe it’s time to go full monty and become fully transparent with a single payment system: one ZIP code, one price, one currency. It’s not about railing against Medicare for all—taxpayers already shoulder 70% of the burden. Instead, we need to decide who should get paid and what we are paying for. If you strip away all the layers of unnecessary steps and costs, good medical care is surprisingly affordable. Ideally, the healthcare dollar should belong with the patient. They go home post-op, and whether they live at an assisted living facility or in a sixth floor walk-up, their social determinants of health are more impactful than their diagnosis code. Yet we reward doctors or their owners when patients recover quickly or remain healthy. It’s no wonder Medicare Advantage patients never get seen. Don’t ask, don’t tell.

If I had a magic wand, I would make all of the healthcare companies become public benefit corporations, with the same tax structure, but the board would have to put public welfare ahead of stockholder profits. That would scare away investors who aren’t meant to be in healthcare. (Think Walmart, CVS, Amazon.) The key is accountability. We all know the cost of care is finite; it’s just held behind an ever-growing paywall.

I’ve spent the last eight years convincing doctors to be accessible and price transparent, and I won’t stop until I have a seat in everyone’s waiting room for a patient who needs it. What I have learned is that if we strip away all the unnecessary steps, medical care is actually better, faster and cheaper than ever before. We just have to put patients first and stop spending money we don’t have to prevent care we can’t stop. It’s up to us to lead the way.

Dr. Muto is a general and vascular surgeon in North Andover, Mass., and the founder and CEO of UBERDOC.

This article is from the March 2024 print issue.

Please log in to post a comment

Dr Muto,

Excellent piece and a situation most of us have been sounding the alarm on for years . The creation of the medical industrial complex has turned out to be just as ominous and fiscal disastrous as the creation of the military industrial complex that Eisenhower warned us about years ago . The corporatization of healthcare where profit is king and shareholder equity reigns supreme over stakeholder (patient) equity driven by the harsh B school practices that are applicable to producing commodities such as refrigerators are not appropriate to the nuances and complexities of healthcare . These have rewarded the merchant class with outrageous salaries , an explosion of costly administrators , onerous facility fees , co pays and deductibles resulting in huge medical debts , increasing personal bankruptcy ,overall precarious hospital balance sheets , decreasing professional moral and increasingly inequitable access and overall poor general population health .

The answer is radical from the bottom up wrestling the system away from the merchant class and returning it to old principles of a sacred calling that first stimulated most of us to take on this noble profession . The care , security and overall health of our population should once again become the preeminent metric of success not the B school balance sheet .

We must as a profession take ownership in this debacle . It is a statement of fact that we as a profession have sold out to this corporate system putting our economic security before that of our patients . As Ben Franklin said so long ago :" He who trades his security for freedom -deserves neither and ends up with neither" . That's where we are but it is never to late to take the ship back - It takes courage and I hope that is not in short supply as is the the time to effect these changes before the whole system implodes which it surely will !

James k Elsey MD FACS

Americans want, and demand, more healthcare expenditures that they are willing to pay for. And if you want to get elected to political office you'd better promise to get it for them. The government mandated and federally paid for (with borrowed dollars) medical industrial complex is a runaway train. We waste SO MUCH MONEY on ineffective care on people who seemingly had little incentive to preserve their own health, or who are at the end of their lives despite the spending of most nations GDP on them in their last 6 months. The cost pressures reverberate throughout the economy, bankrupt the state and federal governments, and are on an ever upward spiral. The dictum that "healthcare is a right" has been used to justify essentially infinite spending. It will not end well.