Dear Fellow Surgical Trainee,

What would you say if tomorrow we could instantly transport you to a program that allowed you to progress through residency based on the quality of your performance, rather than continuing along in your uniform training program lasting five years? As you complete performance metrics, you will transition from intern to junior to chief resident and then graduate with “board-eligible” status to become adjunct faculty.

Does completing general surgery training in four years instead of five sound appealing? This stepwise progression would be based on your ability to complete level-appropriate, clearly described entrustable professional activities or (EPAs).1 As you complete EPAs and your clinical responsibilities increase, you will receive modest raises instead of waiting for your small salary increase just once per year. You would be able to initiate EPA assessments by scheduling performance reviews with your program’s expert faculty. For instance, once faculty assessed your ability to admit, work up and surgically treat a patient with cholecystitis, and they trusted you as a professional to independently manage cholecystitis, your perioperative and operative cholecystitis EPAs would be complete. In addition, a selection of your videotaped operative cases and mini oral board–style simulated case scenarios would be sent to an external expert review panel. This would ensure program adherence to the local EPA assessments.

After successful completion of all the pre-outlined EPAs and associated surgical cases, you would become board eligible. If this occurred before the traditional five-year general surgery time line, you would be hired locally as adjunct faculty, with associated faculty salary and operating privileges. If you needed more time to learn a certain skill set or acquire knowledge of certain procedures or perioperative care pathways beyond the traditional five-year time line, the program would accommodate it accordingly.

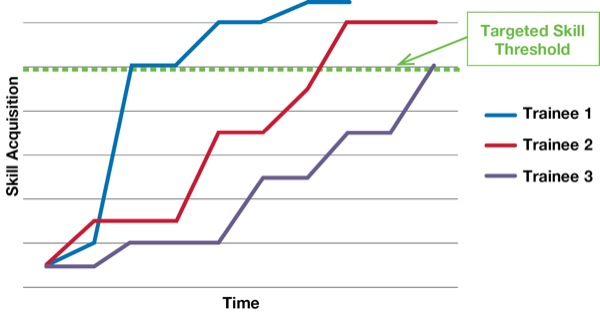

This 2020 general surgery program with merit-based progression might sound far-fetched compared with your current general surgery model of time-based training and promotion, but it is not. It is simply proposing one change in surgical education: transitioning from time-based training to a merit-based system. This system is based on well-accepted educational principles and the understanding that different learners progress along different Ebbinghaus learning curves. Evidence has demonstrated that learners acquire skills and knowledge at different rates (Figure).2,3 This system also uses context-specific assessments, understanding some trainees have difficulty with the transition from factual memorization to clinical context–specific learning and performance.4-6

Such a system might sound too grandiose to implement in 2020, but that has been disproved by our Canadian surgical colleagues.7 Perhaps you are concerned about how your program will provide an adjunct faculty salary if you complete all EPAs and are board-eligible prior to the allotted five-year training time. We can reassure you the extra case volume and RVUs [relative value units] you will bring in as adjunct faculty and the improved OR efficiency your proficient skill set will provide will ensure the chief financial officer’s bottom line remains in the black. The extra patient volume will cover the salary costs of adjunct faculty positions.

As a trainee, you might worry about balancing patient care responsibilities with preparation for the merit-based performance reviews. How will all of the everyday, noneducational activities get completed if residents are away from direct care while studying and practicing technical skill training? This is an important concern and must be addressed for the merit-based system to succeed. Nurses and advanced practice providers will work alongside you in this team-based model to help with patient care responsibilities, paperwork and complex system issues to address the education and service balance. In understanding that learning is a collaborative and social process, this will teach you valuable health care teamwork principles.8,9 An interdisciplinary collaboration EPA will be included in your assessments. In addition, these team members will gain recognition and pride knowing they are contributing to training the next generation of entrustable general surgeons.

I am sure there are several aspects of general surgery training you would like to change. Perhaps you want a better balance between the division of learning and the need to complete noneducational service. Perhaps you are concerned about autonomy in the OR. Perhaps you perceive unfairness in how formative assessments of trainees are completed. Perhaps you have concerns about proper preparation for summative assessments at the end of residency, such as passing your oral or written boards. Perhaps your program has struggled in the past with a trainee who required probation or even was asked to leave surgery. Perhaps you wonder how we can improve attrition rates nationally so that 20% of all trainees who start out in general surgery do not leave for a different medical career, amid the growing general surgeon shortage.10,11 Perhaps you are concerned about the need for fellowship or the inability to be ready for independent general surgery practice when you finish.12 The beauty of this one change—transitioning from time-based to merit-based, trainee-specific progression—is that it addresses many of these concerns. As our program is held accountable through external expert validation of the EPA assessments, our trainees’ time for skill and knowledge acquisition in addition to nontechnical skill development will be prioritized over noneducational service–related activities. In turn, each member of the health care team will be held to a higher standard, and patients—the center of the health care team—will receive better care.

Since Halsted’s 1904 address on “The Training of a Surgeon,” surgical educators have argued the time line of general surgery training is too short, and we must use ingenuity to prepare a competent future workforce.13 As the required skill set and knowledge needed to become an entrustable general surgeon continues to expand, I do not think surgical education ingenuity has kept pace. During this time, general surgery has evolved to incorporate minimally invasive techniques of laparoscopy and robotics; rounds have transitioned from reviewing the paper chart at the patient’s bedside to sifting through hundreds of data points in front of a computer; medical and surgical knowledge have grown exponentially, as has the field of medical education. It is wishful thinking to expect that prior training paradigms will produce trainees ready to operate in a completely different landscape. Medical schools have realized this need for training changes amidst the changing landscape and implemented 13 core EPAs for graduating medical students in 2014.14 It is time for graduate medical education, including general surgery training, to follow suit.

Fellow trainee, I hope you will join me in advocating for this merit-based system. I hope you embrace the challenge of resident-initiated assessments and the operative autonomy that comes with your future adjunct faculty position. Should you take longer than five years to complete the training program, I appreciate your steadfast dedication to becoming a truly entrustable general surgeon and hope that these context-specific objective assessments keep you and your colleagues motivated and deter you from switching into a nonsurgical career. We look forward to watching you progress along your future Ebbinghaus General Surgery Learning Curve and are hopeful that your training will fill the need for the 2020 entrustable general surgery resident.

Sincerely,

Your Fellow Trainee

An Advocate for the 21st Century Merit-Based General Surgery Training Program

References

- Ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-bases training. Med Educat. 2005;39:1176-1177.

- Wozniak RH. Introduction to memory: Hermann Ebbinghaus (1885/1913). Classics in the history of psychology. 1999.

- Grange P, Mulla M. Learning the “learning curve.” Surgery. 2015;157(1):8-9.

- Durning S, Artino Jr AR, Pangaro L, el al. Context and clinical reasoning: understanding the perspective of the expert’s voice. Med Educat. 2011;45(9):927-938.

- Durning SJ, Artino AR, Boulet JR, et al. The impact of selected contextual factors on experts’ clinical reasoning performance (does context impact clinical reasoning performance in experts?). Adv Health Sci Educ. 2012;17(1):65-79.

- Durning SJ, Artino Jr AR, Schuwirth L, van der Vleuten C. Clarifying assumptions to enhance our understanding and assessment of clinical reasoning. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):442-448.

- Nousiainen MT, Mironova P, Hynes M, et al. Eight-year outcomes of a competency-based residency training program in orthopedic surgery. Medical teacher. 2018;40(10):1042-1054.

- Lave JW, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

- Williams TE, Ellison EC. Population analysis predicts a future critical shortage of general surgeons. Surgery. 2008;144(4):548-556.

- Yeo H, Bucholz E, Ann Sosa J, et al. A National Study of Attrition in General Surgery Training: Which Residents Leave and Where Do They Go? Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):529-536.

- Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General Surgery Residency Inadequately Prepares Trainees for Fellowship: Results of a Survey of Fellowship Program Directors. Ann Surg. 2013;258(3):440-449.

- The Training of the Surgeon. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1904;XLIII(21):1553-1554.

- Lomis K, Amiel JM, Ryan MS, et al. Implementing an Entrustable Professional Activities Framework in Undergraduate Medical Education: Early Lessons From the AAMC Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency Pilot. Academic Medicine. 2017;92(6):765-770.

Please log in to post a comment