When it was discovered that Kamila Valieva, the magnificent 15-year-old ice skater competing for the Russian Olympic Committee (ROC), had taken trimetazidine (a fatty acid metabolism blocker and carbohydrate utilization accelerator), a performance-enhancing drug banned by the Olympics, the ROC blamed it on a drug her grandfather was taking. The ROC, the head Russian skating coach Eteri Tutberidze, and the athlete did not accept responsibility for the violation. The grandfather was somehow responsible for her use of his medicine; in other words, the grandfather did it.

I have been a fan of the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings since their inception, and for years was a season ticket holder. In the last few years, my anticipation of their play calling was about 75% accurate. The sideline experts on opposing teams must have done even better. When plays went wrong—which they often did—the commentators, in addition to praising the informed defense, blamed the quarterback for his judgment or passing accuracy, the running back for having been stopped by 800 pounds of muscle, or the receiver for not running the correct route or dropping the ball. Rarely was responsibility placed on the coaching staff who called the plays, until they were fired after the 2021-2022 season. Most rarely did the head coach accept responsibility for the game plan in his post-game press conference.

Failure to accept responsibility is commonplace today in the world we live in. When the heads of a large corporation make a bad decision for a subsidiary company, the leadership of the subsidiary is dismissed and criticized for not “properly” carrying out the mandate they had been given. This phenomenon of passing the buck is also manifest in many aspects of our national and local governments.

Today, medical academia is very much a replica of the corporate world. Faulty decisions by the “senior leadership,” the dean, the subdeans and the sub-subdeans, are blamed on the department or division heads. In turn, these quasi-leaders try to avoid making innovative decisions in order to stay under the radar and maintain their positions. This abrogation of responsibility is the progenitor of stagnation in healthcare progress.

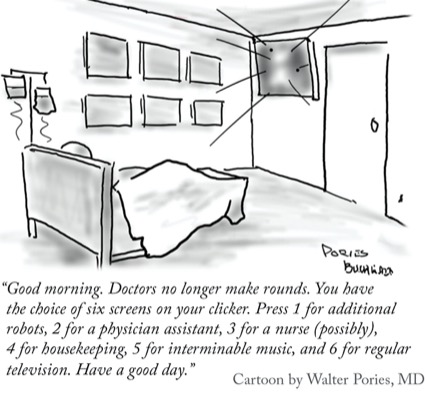

Avoiding responsibility has become the hallmark of today’s practice of healthcare. The first step in this process is evading personal communication. No patient can talk to a doctor by telephone without first talking to robots while listening interminably to elevator music, and eventually being interrogated by a clerk or occasionally a nurse. Few patients, other than those willing and able to pay a ransom for concierge medicine, even have a doctor. Patients rely on a group of interchangeable players with interchangeable hours. They are the recipients of team, group, service-line, committee medical decisions and therapy, wherein each specialist makes a singular contribution to a patient’s care—a process comparable to an industry assembly line. This system has broken the time-honored doctor–patient relationship. Starting with Hippocrates, this relationship has been based on mutual trust, with a physician taking responsibility for the needs of his or her patient. The terms “my doctor” and “my patient” represent the acceptance of a moral contract. This bond has been broken because it is antithetical to corporate medicine.

This abrogation of personal responsibility now exists in our discipline of surgery. The majority of today’s surgeons are employees of a hospital or a healthcare conglomerate, and have traded taking responsibility for individual patients for certain lifestyle advantages. They have become part of service-line medical care under the authority of a CEO or dean.

The cardinal assemblies of our profession are the grand rounds and mortality and morbidity (M&M) conferences. In the latter, we discuss our complications and our failures. It is an occasion for all present to learn from mistakes and misjudgments, a teaching opportunity for both surgical neophytes and veterans. This conference pays our respects, at times the last respects, to patients injured by the events being presented.

In the past, it was rare for a neighbor at an M&M to say to me, “That’s not the patient I knew,” as the discusser fabricated to cover his or her errors. Fabrication has become more commonplace, as has blaming others or the elements or the system for a technical error, faulty judgment—in essence, any adverse event. Once, after several repeated episodes by a surgical resident of blaming others instead of assuming blame, I rose and said, “It is uncanny that God hates you so much.”

This loss of individual ethical standards arises from the existing system of patient care. A confession of error is now cause for a negative grade assessment by the external organizations that determine national standing, and possibly income. A confirmatory, complementary, institutional administrative decision is the policy of avoiding blame for the readmission of a patient with a complication. It is not unusual for a patient returning with an obvious wound infection to be admitted to a nonsurgical service as “a fever of unknown origin,” rather than being readmitted to the surgical service that created the complication.

When I was still an active surgeon, I instructed every resident on arriving on my service that I would hold him or her personally responsible for any adverse event that befell a patient in their care. I emphasized this admonition by an example: “If a patient on narcotics or comparable medications falls out of bed at night, it is your fault for not having ordered guardrails.” I was trying to train surgeons to assume responsibility as an ingrained habit for future operative planning, execution and postoperative patient care.

When I was in the Strategic Air Command, U.S. Air Force, the acceptable first response when questioned about a flight incident, or any adverse event, was “My fault, sir!” This practice not only applied to decisions made but in cases where the plane was hit by lightning or the landing gear collapsed. Except for purposeful practice weather flights, lightning clouds could be avoided and landing gears inspected before takeoff. A Board of Inquiry followed an incident, and after a detailed accounting of events, the most common verdict was “Pilot error.” This standard policy for inculcating personal responsibility was designed to provide the nation with responsible service officers.

The basic education of a surgeon takes 13 years: four years of college, four years of medical school, five years of residency, which is commonly augmented by two to five additional years of fellowship or research—for a potential total of 15 to 18 years. At this point, the surgical trainee is in his or her 30s, and may have a growing family. What is the universal graduation gift, besides financial concerns, for the newly designated, probably board-certified surgeon? It is independence—that is, taking responsibility for one’s actions. For a surgeon, this independence is exemplified by stepping into the operating room for the first time with no attending surgeon for cover. Such a precious gift should not readily be denigrated by servitude to an administrative body. With this gift of personal independence comes the acceptance of responsibility for others. If independence is forfeited, responsibility for decisions, actions and outcomes also perishes.

What does this gift of independence generate in addition to the best patient care? It is the basis for surgical progress. In the 30 years from 1930 to 1960, at the University of Minnesota Department of Surgery (“fly-over land” to many), under the leadership of Owen H. Wangensteen, the following occurred: reduction in mortality for bowel obstruction from 40% to 4%; the introduction of open-heart surgery using a pump oxygenator, the basis for heart transplantation; the first pancreas transplantation; the partial ileal bypass operation for hyperlipidemia; the background studies for the first National Institutes of Health–funded randomized controlled trial using metabolic surgery that demonstrated atherosclerosis retardation and regression; the first bariatric surgery procedures; and other surgical contributions. These halcyon days have been documented in a book titled “Surgical Renaissance in the Heartland: A Memoir of the Wangensteen Era” (Buchwald H. University of Minnesota Press; 2020).

In this article, I have tried to provide some thoughts for reflection and a perspective on personal responsibility. The concept of “Grandfather did it” is not limited to the ROC; it has become commonplace in our everyday world. It dominates our healthcare delivery and has invaded our discipline of surgery. Can we reestablish professional independence and responsibility? Do we, as a discipline, want to?

Dr. Buchwald is a professor of surgery and biomedical engineering, and the Owen H. and Sarah Davidson Wangensteen Chair in Experimental Surgery (emeritus), at the University of Minnesota, in Minneapolis. His articles appear every other month.

Editor’s note: Opinions in General Surgery News belong to the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the publication.

This article is from the April 2022 print issue.

Please log in to post a comment