When the COVID-19 pandemic started to accelerate and spread, American health care responded by consolidating and isolating hospital beds and ICUs. American surgery continued to perform emergency operations, but canceled cases considered elective. Many surgical units and many surgeons, not needed or qualified as intensivists, were unemployed. Subsequently, for economic concerns as well as for humane dedication, elective surgery was segmented into urgent (e.g., cancer surgery) and not so urgent (e.g., cosmetic surgery). With increasing surgical inactivation and the indefinite extension of the COVID-19 pandemic, many formerly elective procedures have gradually been allowed to be added to the operating room schedule.

Where does metabolic/bariatric surgery belong in the spectrum of emergency, urgent and elective surgery, especially if elective surgery is defined as free of health risks by a prolonged wait?

One categorization of elective operative procedures is to classify them as reparative, prophylactic, curative and lifesaving, with some operations overlapping several categories. Of the most common operative procedures performed in the United States, many are orthopedic and reparative in nature, such as knee arthroplasty. Certain reparative procedures are prophylactic as well, such as coronary artery bypass grafting, and some are primarily prophylactic, like colonic polypectomy; others are curative, an example being closure of a patent ductus arteriosus. There are also a few procedures that can be said to qualify as lifesaving, such as early breast cancer surgery.

Today the number of metabolic/bariatric operations performed in the United States annually is about 250,000, just short of the number of cholecystectomies at 300,000. Thousands of articles, over six decades, have been published in the peer-reviewed literature, including numerous randomized controlled clinical trials and systemic reviews and meta-analyses, demonstrating metabolic/bariatric surgery efficacy, safety, resolution of obesity comorbidities, improvement of quality of life and increasing life expectancy. Metabolic/bariatric surgery procedures clearly are reparative, prophylactic, curative and lifesaving concurrently. Further, the disease of obesity with its comorbidities, unless treated by metabolic/bariatric surgery, is a malignancy that robs the afflicted of the pleasures of life en route to a premature death.

Metabolic/bariatric surgery is certainly reparative. It converts morbid obesity to lesser obesity, overweight, or at times, normal weight. It resolves up to 70% to 90% of the metabolic diseases of type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia and hypertension—the precursors of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease—as well as mitigating the anatomic orthopedic and sleep apnea problems associated with obesity. It cures skin eruptions. It restores normal menstrual and reproductive functions. It reverses non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. It improves exercise tolerance and quality of life. It has even been shown to improve mentation.

Metabolic/bariatric surgery is prophylactic, serving to prevent the metabolic syndrome and the other problems listed above when they are in their early stages or prior to becoming manifest. The evidence is definitive that metabolic/bariatric surgery markedly lowers the incidence rates of several cancers.

If the disease of obesity is no longer manifest; if type 2 diabetes, once present, does not recur; if lipids are permanently lowered; if high blood pressure is reduced; if sleep apnea is relieved; if walking and other daily activities are improved—we can truly say that metabolic/bariatric surgery deserves to be considered as curative.

Combining the repairs, cures, resolutions and functional improvements generated by metabolic/bariatric surgery, in particular pertaining to cardiovascular processes, it is reasonable to assert that metabolic/bariatric surgery is lifesaving. Literature proof of increased life expectancy after metabolic/bariatric surgery may be found in the current paper from the cardinal Swedish Obese Subjects Study (N EngI J Med 2020;383:1535-1543), in support of well over a dozen previous publications providing hard data for the same conclusion.

Yet, certain of our internist colleagues would diminish the therapeutic impact of bariatric surgery and, thereby, increase the deadly outcomes of obesity, by linguistic minimization. These internists will only publish the work of metabolic/bariatric surgeons if they do not use the term “morbid obesity,” and instead substitute “severe obesity.” However, they have no difficulty with “malignant hypertension,” or “end-stage heart failure”—conditions amenable to medical therapy. Recently, these semanticists have asked us not to refer to the “obese patient,” comparable to the manner in which they feel free to speak of the “cancer patient” or “diabetic patient,” in order to emphasize the seriousness of these afflictions. They prefer that we use instead, “the patient with obesity,” as if obesity were an attached attribute and not characteristic of a state of great ill health and diminished life expectancy, a disease not an ancillary trait, a disease curable by surgery.

Language is not a trivial matter. Words reflect reality and also shape reality. If we diminish the impact of obesity, we remove it from being considered a disease, truly a morbid disease, to being a social subject of diversity. We cannot sacrifice truth in language because such an acquiescence is a major disservice to our patients. We must not be persuaded by “internists with hypocrisy.”

The definition of metabolic surgery as “the operative manipulation of a putatively normal organ or organ system to achieve a biological result for a potential health gain” (Buchwald H, Varco RL. Metabolic Surgery. Grune & Stratton; 1978) has found general acceptance. In addition to bariatric surgery, this discipline encompasses gastrectomies and vagotomies for peptic ulcer disease, splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenia, portal diversion for glycogen storage disease, endocrine ablations for metastatic malignancies, pancreas transplantation for diabetes, carotid body ablations and sympathectomies for hypertension, and partial ileal bypass for hyperlipidemia, as well as perirenal neuroablation and gastric stimulation for diabetes, cervical single vagus nerve stimulation for refractory depression, and several non–weight-losing gastrointestinal operations designed to mitigate type 2 diabetes. Indeed, truly bariatric procedures, including the Scopinaro biliopancreatic diversion, have been demonstrated to eliminate type 2 diabetes with minimal weight loss in overweight but not obese patients.

Certain metabolic operative procedures are elective in the sense that they can wait to be performed without a definitive threat to health or life. Metabolic/bariatric surgery is definitely not among them. Once a metabolic/bariatric operation is decided upon, it belongs in the urgent category. This conclusion is warranted by the vast, powerful, statistically significant data available in the literature. This conclusion is even more justified in the COVID-19 pandemic era.

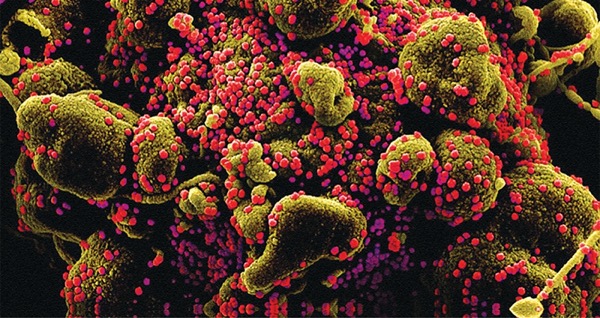

It has been well documented that obesity, diabetes and hypertension are primary risk factors for the severity of, and mortality from, COVID-19. In essence, these factors equate to the metabolic syndrome, a manifestation of the disease of morbid obesity, best and successfully treated by metabolic/bariatric surgery. If there were a pill or an injection that could achieve the reparative, prophylactic, curative and lifesaving results of metabolic/bariatric surgery, every physician, federal and state governments, the media and the public would unanimously advocate this therapy. The natural human fear of and reluctance to undergo any form of surgery is universal. That fear has impeded the consideration of using metabolic/bariatric surgery as an equivalent to nonsurgical management. While it is, of course, impossible to operate on the entire population that might benefit from surgical therapy, it is feasible to operate on that fraction of patients most in need of its benefits. Metabolic/bariatric surgery, therefore, is urgent surgery during the COVID-19 era.

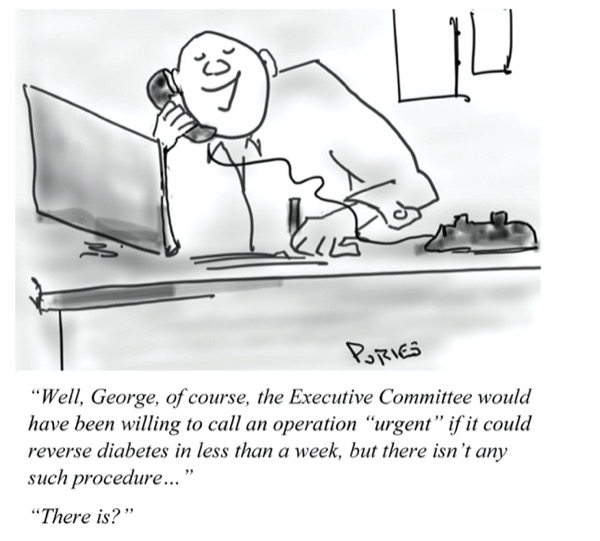

It will be argued that weight loss takes time, but we must consider that the COVID-19 pandemic will last for a considerable period of time as well—at least two years—and the recurrence of a vaccine-resistant pandemic surge is possible, as well as future highly infectious viral pandemics. In addition, type 2 diabetes reversal—“cure”—occurs days after the operative metabolic/bariatric surgery procedure (Ann Surg 1995;222[3]:339-350). Hypertension and hyperlipidemia also respond rapidly; blood pressure and blood lipid concentrations normalize within weeks.

Currently, an American College of Surgeons outreach initiative exists to acquaint surgeons, physicians and the public with both the concept and applications of metabolic surgery. The organization is also advocating a staggered, intelligent return to the operating room. In selecting the elective operative procedures for this affirmative transition, metabolic/bariatric surgery—for its prophylactic, curative and lifesaving effects—should be considered as urgent.

Dr. Buchwald is a professor of surgery and biomedical engineering, and the Owen H. and Sarah Davidson Wangensteen Chair in Experimental Surgery (emeritus), at the University of Minnesota, in Minneapolis. His articles appear every other month.

This article is from the December 2020 print issue.

Please log in to post a comment