—By Caroline Helwick

San Diego—The 2012 U.S. Multi-Society Task Force set guidelines for surveillance intervals following colonoscopy, but adherence to the recommendations continues to be suboptimal.

Two studies reported at the 2019 Digestive Disease Week found that surveillance intervals often are too short, possibly putting patients at risk for harm from unnecessary interventions.

In one analysis, Wayne State University researchers examined whether endoscopists from three Detroit practices adhered to the 2012 recommendations (abstract Sa1065).

Ahmad Abu-Heija, MD, and his colleagues reviewed 1,132 colonoscopy reports. Of these, 540 were performed by academic gastroenterologists, 136 by nonacademic gastroenterologists and 81 by surgeons.

The overall rate of adherence to guidelines was 59%, but peaked at 72.8% for academic gastroenterologists. Adherence was poor for the other two providers: 32.4% for nonacademic gastroenterologists and only 12.3% for surgeons (P<0.001).

Endoscopists specified a clear interval for surveillance in 80.7% of reports, although academic gastroenterologists were more likely to do so than other clinicians (93.5%, 56.6% and 35.8%, respectively; P<0.001).

A longer surveillance interval was recommended in 5.2% of reports, including 5.7% by academic gastroenterologists, 5.1% by nonacademic gastroenterologists and 1.2% by surgeons (P<0.001). Among the 304 colonoscopies without detected polyps, surgeons recommended an interval that was too short in 25.5% of cases.

“Our findings are consistent with literature demonstrating lack of adherence to current guidelines set forth by gastroenterology societies. This disaccord can expose patients to either unnecessary harm or the risk of developing interval malignancy,” Dr. Abu-Heija said. “Significantly more evidence—now more than ever—is supportive of the 10-year protection offered by a colonoscopy performed in an adequately prepared colon in an average-risk person,” Dr. Abu-Heija said.

However, overuse of medical procedures remains a significant contributor to the high cost of health care, Dr. Abu-Heija noted. “The false premise of ‘might help, can’t hurt’ should rather be rephrased as ‘can hurt, might not help,’” he said.

In Safety Net Health System, Intervals Too Short

Surveillance recommendations were more likely to be too short in a study of 1,709 individuals treated within a safety net health system, according to Jaison Santhosh John, MD, of the University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School (abstract Tu1653). His study found that 28% of surveillance recommendations lacked agreement with the 2012 USMSTF guidelines based on a second review of the index colonoscopy outcome. Of these, almost 20% were too short.

“We found moderate differences between initial provider and secondary reviewer recommendations for surveillance interval. Providers tended to recommend shorter intervals—mainly, five years versus five to 10 years—which could lead to unnecessary earlier colonoscopies and place a strain on resources in this safety net health system,” Dr. John said. “Adherence to these guidelines is especially important in safety net care systems to ensure effective colon cancer prevention and utilization of limited resources. In this vulnerable population, where there’s not a lot of resources, this is especially important.”

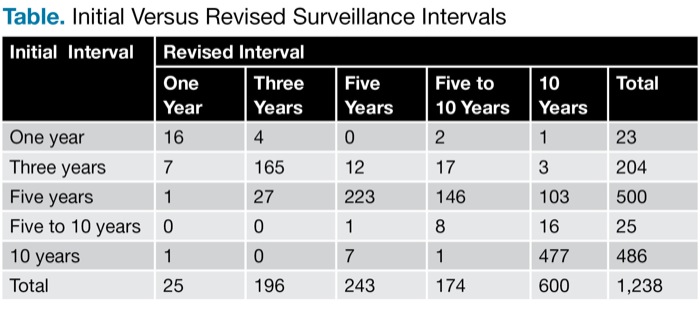

Dr. John’s analysis was based on a chart review of 1,238 patients who underwent colonoscopy within the past 10 years. Trained reviewers determined the number and size of polyps with pertinent pathology, family history of colorectal cancer, and the provider’s initial recommendations for follow-up. The reviewers used USMSTF guidelines to create a revised surveillance interval for comparison with initial recommendations.

The initial surveillance interval was clearly stated in 70.2% of cases; among this group the recommended intervals were too short in 18.4% of cases and too long in 2.7%. Of 1,238 patients, the initial recommendations of providers were correct in 889 (72%) cases (Table).

| Table. Initial Versus Revised Surveillance Intervals | ||||||

| Initial Interval | Revised Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Year | Three Years | Five Years | Five to 10 Years | 10 Years | Total | |

| One year | 16 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 23 |

| Three years | 7 | 165 | 12 | 17 | 3 | 204 |

| Five years | 1 | 27 | 223 | 146 | 103 | 500 |

| Five to 10 years | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 16 | 25 |

| 10 years | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 477 | 486 |

| Total | 25 | 196 | 243 | 174 | 600 | 1,238 |

Better adherence to evidence-based follow-up intervals can make the use of resources more efficient within the safety net care system, Dr. John said. The researchers now plan to reschedule the 28% of patients whose surveillance intervals were not in accordance with the guidelines.

Why the Lack of Adherence?

Samir Gupta, MD, MS, an associate professor of medicine at UC San Diego Health, said lack of adherence to surveillance guidelines is common, and the reasons vary. “In the best-case scenario, the patient is given a shorter interval because the bowel prep wasn’t good,” Dr. Gupta told Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News. “A longer-than-expected interval could be the result of lack of knowledge by the doctor. Most worrisome, though, is that the physician just wants to make money, and you make more when you bring people back more frequently. That’s a real thing.”

Improvements in the “overuse issue” must be “driven through the insurance companies,” he said. “Education will fix that only a tiny bit.”

Another way to improve adherence to proper surveillance intervals, Dr. Gupta said, is for practices to institute a standard workflow for reporting the results of biopsies. “We instituted standardized workflows at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas [where he previously practiced]; it really improved our correct recommendation rate,” he said. “I replicated that later at our VA [VA San Diego Healthcare System], and it basically got us to about 95% guideline compliance.”

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, in Minneapolis, and the GI section chief of the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, agreed that surveillance intervals that are unduly short “are a problem.

“When we were starting learning about surveillance intervals, we erred on the shorter side,” Dr. Shaukat said. “For example, the National Polyp Study compared one-year versus three-year surveillance intervals for adenomas [N Engl J Med 1993;329[27]:1977-1981]. However, 20 years later we have higher-quality colonoscopies and also have accumulated evidence that reassures us that too-short surveillance is not only unnecessary but may be dangerous. It exposes the patient to undue risk of complications without added protective benefit, making it low-value care.”

Nonetheless, there are barriers to adherence to the recommendations, Dr. Shaukat said. These include endoscopists’ doubts about the quality of the exam, concern for medicolegal issues, and financial incentives to perform more colonoscopies. “It will take a concerted effort from payors, providers and patients to make the necessary changes required,” she said.

Drs. Abu-Heija, John and Shaukat reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Gupta has consulted for Progenity.