Introduction by Steven D. Wexner, MD, PhD (Hon)

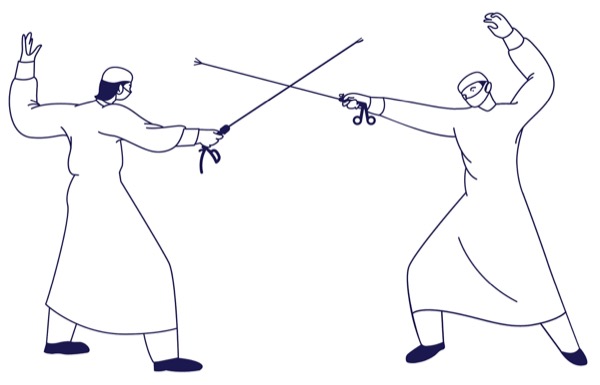

I am appreciative that Colleen Hutchinson again asked me to “volunteer” friends to engage in this year’s edition of “Dueling Debates in Colorectal Surgery.” Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, I have selected three of the four topics as germane to COVID-19, leaving the fourth subject as more generic within colorectal surgery.

This year’s debates commence with two diametrically opposed views on whether or not laparoscopy can be safely used in patients infected with COVID-19. Dr. Abe Fingerhut, from France, offers his very cogent logic as to not only why, but how, laparoscopy can be safely employed in patients infected with COVID-19. The contrary view is espoused by Dr. Art Hiranyakas from Phuket, Thailand. Dr. Hiranyakas cites excellent evidence about corollary situations, such as human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and papillomavirus, as well as hazardous particulate matter in smoke. Both of these experts are very passionate about their views.

The second question was whether negative-pressure operating rooms should be used for patients infected with COVID-19. Dr. Delia Cortés-Guiral, from Madrid, Spain and Saudi Arabia, cites very sound logic as to the reasons for the employment of a negative-pressure OR. The opposing viewpoint is taken by Dr. Amy Lightner, from Cleveland, who invokes the absence of published evidence suggesting that negative-pressure rooms prevent the transmission of the coronavirus. Both of these experts are well versed in the literature and engage in a lively debate.

The third topic is whether or not all patients should be tested for COVID-19 infection before commencement of elective surgery. Dr. Aneel Bhangu, from Birmingham, England, notes that the consequences of postoperative COVID-19 pneumonia are “so devastating” that testing is indeed vital. Dr. Jacob Izbicki acknowledges that the German government currently requires routine testing of all patients before elective surgery and indeed concedes that testing can be an effective tool; however, he also cites the literature showing high false-negative rates of these tests and touches on the potential for repeat testing as being needed.

The last question focuses on a topic not specific to COVID-19:the treatment of T1N0 rectal cancers. Dr. Emre Gorgun, from Cleveland, presents his view on why endoscopic submucosal dissection is the best treatment for T1N0 cancers, focusing on the organ preservation aspect of that approach. Dr. Dana Hayden, from Chicago, notes that she “wholeheartedly” disagrees. She bases her sentiment on the fact that T1 cancers may have spread to lymph nodes and that these lymph nodes may not be identified on MRI.

I thank each of these debaters for their time, expertise and viewpoints. I hope that readers of General Surgery News enjoy their lively comments as much as I did.

Dr. Wexner is the director of the Digestive Disease Center and chairman of the Department of Colorectal Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Florida, in Weston.

As we’ve done since 2010, Dr. Steven Wexner and I have collaborated on the annual “Dueling Debates in Colorectal Surgery.” With special thanks to Dr. Wexner for lending his time, expertise and opinion, I present current debates in colorectal surgery, including COVID-19 related issues in colon surgery, such as use of laparoscopy in infected patients, negative-pressure operating rooms for patients with COVID-19, and COVID-19 testing for patients before elective surgery, as well as whether T1N0 rectal cancers are best treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Read on, take a side, access On the Spot online, and share your view with a comment. Also, check out Gut Reaction on page 14 for these surgeons’ candid takes on artificial intelligence, fluorescence imaging, mental conditioning, single port for transanal TME, and the worst complications they’ve seen in their recent cases.

Feel free to send me feedback at colleen@cmhadvisors.com. Stay safe and healthy, and happy reading!

—Colleen Hutchinson

Colleen Hutchinson is a medical communications consultant at CMH Media, based in Philadelphia. She can be reached at colleen@cmhadvisors.com.

Laparoscopy should be used in patients infected with COVID-19.

| Section for Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Medical University of Graz, Austria; Department of General Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai; Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai Minimally Invasive Surgery Center |

| Director of Bangkok-Phuket Colorectal Disease Institute at Bangkok Hospital Phuket, and Director of Colorectal Surgery Clinic, Bangkok Hospital Headquarters |

Dr. Fingerhut: Agree, but I need a caveat: The word “should” in the statement might sound like a recommendation, which we cannot make. Let me say this:

There is not one scrap of evidence proving that surgical smoke created in laparoscopy is more dangerous than that created by the same energy-driven instruments on the same target organs during laparotomy.

No one has ever been able to isolate SARS–CoV-2 in the aerosol (of laparoscopy), and experiments that found that the virus is viable in aerosols were in closed cylinders, not the human body.

In contrast to laparotomy, surgical smoke created during laparoscopy is contained within a “closed” abdominal cavity, and as such does not diffuse into the OR during the operation (as is the case for laparotomy).

Precautions and strict observance of common sense “should” ensure that the aerosol created during laparoscopic surgery does not escape inadvertently during the operation (airtight trocar incision, air-tight valves in good working condition, no venting during operation to get rid of smoke, careful and steady insertion and withdrawal of instruments, use of one of the modern systems to ensure closed circuit flow and filtered evacuation of laparoscopic carbon dioxide), and, obviously, that the pneumoperitoneum should be completely evacuated before specimen extraction or final withdrawal of trocars for abdominal closure. Accessorily (and perhaps more debatable), there should be low-pressure pneumoperitoneum, short bursts of low-intensity energy.

To conclude, if there is no other contraindication, there is no reason why “laparoscopy should not be used in patients just because they are infected with COVID-19.”

Dr. Hiranyakas: Disagree. According to current evidence, COVID-19 virus is primarily transmitted between people through respiratory droplets (particles >5-10 mcm in diameter) and contact routes. The World Health Organization stated that airborne transmission of COVID-19 may be possible in specific circumstances and settings in which procedures that generate aerosols are performed. It is crucial for surgeons to understand that airborne transmission is different from droplet transmission as it refers to the presence of microbes within droplet nuclei (particles <5 mcm in diameter) that can remain in the air for long periods of time and be transmitted to others over distances greater than 1 m.

All energy devices, including electrocautery and ultrasonic in nature, will produce surgical smoke, which is aerosolized when used on tissue. Despite the fact that the respiratory viruses are not known to be transmitted by blood, studies have shown that some activated viruses like HIV, hepatitis B virus and papillomavirus can survive in surgical smoke and be potentially infective (Surg Endosc 1998;12[8]:1017-1019; J Med Virol 1991;33[1]:47-50; Occup Environ Med 2016;73[12]:857-863). Although the use of electrocautery in open surgery is potentially hazardous, particle concentration of the smoke in laparoscopic surgery was shown to be significantly higher due to low gas mobility in the pneumoperitoneum (Ann Surg 2020 Mar 26. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003924; J Air Waste Manag Assoc 2020;70[3]:324-332). It is also important to address that the virus may concentrate in the gastrointestinal tract even though the respiratory system is sealed by a closed and filtered respiratory circuit.

With the very little evidence regarding the relative risks of minimally invasive surgery versus the conventional open approach specific to COVID-19, the need to protect caregivers from infection and preserve hospital capacity is one of the top priorities of concern. Physicians typically focus on the patient’s risk, not our own. In an infectious disease pandemic, the degree of uncertainty renders calculated risk–benefit analyses impossible. Our calculus must incorporate our own exposure risk, and how exposure would limit the ability to care for future patients.

With the very little evidence regarding the relative risks of minimally invasive surgery versus the conventional open approach specific to COVID-19, the need to protect caregivers from infection and preserve hospital capacity is one of the top priorities of concern. Physicians typically focus on the patient’s risk, not our own. In an infectious disease pandemic, the degree of uncertainty renders calculated risk–benefit analyses impossible. Our calculus must incorporate our own exposure risk, and how exposure would limit the ability to care for future patients.

Negative-pressure operating rooms should be used for patients with COVID-19.

| Surgical Oncologist, European Certification on Peritoneal Surface Oncology; Consultant Peritoneal Surface Malignancies and Colorectal Surgeon, King Khalid Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

| Associate Professor of Colorectal Surgery, Digestive Disease Institute; Associate Professor of Inflammation and Immunity, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic Disclosure: Consultant for Takeda |

Dr. Cortés-Guiral: Agree. Protection of caregivers in the OR has been a major concern since the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak and negative-pressure ORs, anterooms and endoscopy suites have been recommended as the safest option to treat COVID-19–positive or suspected patients. Negative-pressure rooms protect not only personnel inside, but also patients and personnel in the adjacent areas because the lower air pressure in the OR prevents air to flow from the negative-pressure room to the contiguous ones. Active replication of SARS-CoV-2 has been proven to occur in the stomach, duodenum and rectum, and one case report informed us about the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the peritoneal fluids; however, further research on contagiousness capability by the virus from smoke or pneumoperitoneum droplets is required.

Under the suspicion that coronavirus particles could be released during laparoscopy with carbon dioxide, a number of recommendations for safe laparoscopic procedures have been provided by the main surgical societies (American College of Surgeons, European Society of Surgical Oncology, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons and others), such as the use of devices to filter released CO2 for aerosolized particles, limiting the intraabdominal pressure, reducing the electrocautery settings, and, accordingly during laparotomy, careful evacuation of the resultant smoke must be ensured. In both cases, a negative-pressure OR obviously looks fundamental to achieve this safety goal. The moment of extubation is especially risky and it is also recommended to do it in a negative-pressure OR.

Interestingly, engineers from Hong Kong have demonstrated that a positive OR could be modified and converted to a negative one, and many guidelines suggest as the optimal location for the negative-pressure OR, a corner of the surgical area with separate access. In brief, a negative-pressure OR is a protective measure as essential as personal protective equipment that could effectively protect not only everyone inside, but also other health care workers and patients around.

Dr. Lightner: Disagree. There is no published evidence to suggest negative-pressure rooms will prevent the transmission of COVID-19. This reflects much of what we have done—react and quickly implement policy, with the intention of doing all that is possible to keep patients and providers safe. However, if we overreact and implement policies without supporting data, we can also cause secondary consequences.

Some hospitals may not have negative-pressure rooms. Should a COVID-19 patient with peritonitis then be transferred to another hospital just for a negative-pressure room? Will we cause more postoperative infectious complications in the non–COVID-19 patients exposed to negative pressure? Is it practical to convert ORs to negative pressure?

While it is certainly reasonable to consider all available options to prevent the spread of COVID-19, there may be simple higher impact changes, such as reducing OR and anesthesia staff changes mid-operation and stopping traffic through the OR that causes repeated opening and closing of doors. These changes may be more effective in reducing spread of COVID-19 and require less infrastructure to implement. Until we have more data, the use of all measures to promote safety is valued, so long as all the secondary consequences are evaluated in parallel.

All patients should be tested for COVID-19 before elective surgery.

| NIHR Clinician Scientist in Global Surgery; Honorary Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, University Hospital Birmingham, United Kingdom; @COVIDSurg Chief Investigator |

| Surgeon in Chief, Chairman of the Department of General, Visceral and Thoracic Surgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany |

Dr. Bhangu: Agree. The consequences of a postoperative COVID-19 pneumonia are so devastating that testing in affected areas will become vital. Most postoperative deaths after elective surgery we will see during this era will be driven by postoperative complications, which in turn are driven by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although their incidence will wax and wane as surges come and go, the effects of just one of these deaths in an elective surgical patient will change practice.

Most European Union and North American areas have been hit hard, meaning testing will identify some patients who are asymptomatic carriers and will benefit from deferred surgery. If the rates of community SARS-CoV-2 infection decline to negligible, testing strategies can be relaxed, but we don’t know what the post-peak world holds.

There are so many questions around testing that we then need to answer—who, when, where. Bringing a patient into a COVID-hot hospital for a CT scan or swab may expose them to SARS-CoV-2, generating more risk than benefit. I hope all surgeons around the world will start working as broad, networked teams to find local pathways that work.

Dr. Izbicki: Disagree—by order of the government [in Germany], we are currently obliged to test all patients before elective surgery.

Routine testing of all patients can be an effective tool, but its effectiveness depends on the specific regional pandemic situation. In a potential future scenario, with a majority of COVID-19–positive patients, the routine testing of all patients might not have a beneficial effect; neither might the routine testing in a controlled pandemic situation with a stable reproduction value below 1 be beneficial.

In the end, a regional local pandemic status with a doubtful tendency seems to be the most relevant scenario, where routine testing of all patients will be helpful to avoid a spread of COVID-19 within the medical institution. Even in this scenario, we have to remember that the test result is a snapshot of the current situation. Therefore, routine testing of all patients has to be done right before hospitalization for surgery in order to be effective, and the patients have to be isolated until the test results arrive or an admission will take place after a negative test result is assured.

Taking into account the incubation time of up to 14 days and the high false-negative test rates (as high as 30%), even a negative test does not negate the possibility of an infection (JAMA 2020 Mar 11. [Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786). Therefore, a recently published testing recommendation for elective surgery patients includes repeated testing every week of the hospital stay and at discharge (Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020 Apr 13. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.04.014).

In summary, the pandemic situation dictates the necessity of routine testing. If routine testing is carried out, it has to be done before and during hospitalization, and at discharge, to be as effective as possible.

T1N0 rectal cancers are best treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection.

| Krause-Lieberman Chair in Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery, Director of EndoLumenal Surgery Center, Lower GI, Cleveland Clinic, Digestive Disease Institute, Cleveland Disclosure: Consultant for Boston Scientific, Cook, Lumendi |

| Associate Professor, Colon and Rectal Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago |

Dr. Gorgun: Agree. The treatment of early rectal cancer is challenging, since the lymph node involvement can only be verified after oncologic resections. Modalities of local resection are possible treatments in cases where there is little chance of lymph node involvement. Long-term oncologic outcomes are comparable between organ resection techniques and local excisions. Clearly, local resections are superior in terms of morbidities and functional outcomes. Although studies comparing endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and other local excision techniques (transanal endoscopic microsurgery and transanal minimally invasive surgery) are limited, ESD has been shown to be an excellent approach, in expert hands, that can overcome some of the limitations of other local excision techniques.

Advantages are not only limited in that ESD can be performed under conscious sedation—as well as being effective on lesions located above or near the anal verge—but also, ESD does not destroy anatomic planes since it involves only partial thickness of the target organ. Furthermore, based on the final pathology, if a patient requires reconstructive organ resection (proctectomy/low anterior resection), TME and anastomosis planes would remain intact. Additionally, for larger laterally spreading tumors covering more than two-thirds of the lumen, extensive tissue resection via ESD provides fast healing of the resection area with excellent “re-epithelialization.” This yields low complication rates and superior functional outcomes compared with other full-thickness local excision techniques. After expertise level has been reached, ESD procedures can be performed in the endoscopy suite under sedation, with results of shorter length of hospital stay and significant cost savings in health care.

Dr. Hayden: I wholeheartedly disagree. My disclaimer: I fully confess to be an “over-treater” and preventative surgeon. I have seen rectal cancers understaged during initial workup. I have seen T1 cancers have node-positive disease indicated on final pathology that was not identified on MRI. Radiation oncology will then recommend adjuvant radiation, as they should, since it is still the standard of care. Then our beautiful, healthy, nonleaking colorectal anastomoses will be exposed to radiation, leading to strictures, poor function and other complications.

I do admit, local excision for T1 cancers has a role for poor surgical candidates and patients with extremely low cancers leading to permanent colostomy. However, with submucosal resection alone, the perirectal lymph nodes are not addressed. Then we are left with wishful thinking that our patient will fall into the lower range of potential lymph node metastases for T1 cancers. We have one great shot to treat rectal cancer appropriately and it is best performed at the first treatment.