Montefiore Medical Center

New York City

Let us publicly release all of the data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual surveys and assessment of surgical trainees in the United States. Incomplete evidence is presented year after year in the Medscape annual “Resident Lifestyle & Happiness Report” and “National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report.” The yearly statistics are irrelevant. Many residents and surgeons were objectively unhappy, and many are still unhappy. The etiology of this disillusionment is the same set of culprits that plagues us all: administrative tasks, work hours, compensation, etc. I groan every time I am made to bear witness to this timeless pessimism without recourse.

In spite of all the available evidence, a thick cloud of mystery hangs overhead and we in the community remain estranged from the problems facing us. Fortunately, a solution has already been proposed by the science fiction author Douglas Adams in “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” In the story, we are told that the answer to life, the universe and everything is the number 42. We and the novel’s protagonists are alike in that we do not know the right question.

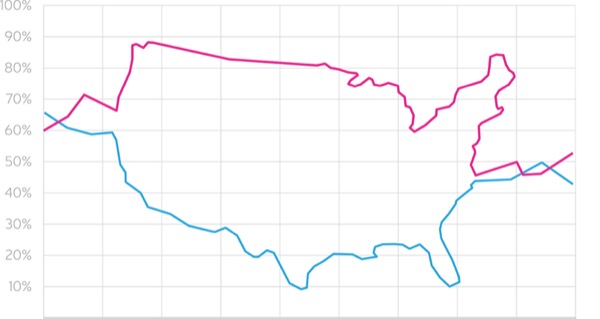

What do we know? Based on the ACGME “Data Resource Book” for the academic year 2017-2018, there were 301 accredited general surgery programs with a total of 8,475 active residents, with a median size of 26 residents and mean first year age of 29 years. Residents were predominantly male (58.3%) and white (45.8%), compared with women (37.9%) and residents of other backgrounds (Asian or Pacific Islander, 12%; Hispanic/Latino, 4.6%; Black non-Hispanic, 3.9%; and other or unknown, 33.4%). The distribution of residents in general surgery and subspecialties was disproportionate across the country. The District of Columbia was the best represented across all specialties, with 198 residents per 100,000 people. This was followed by Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New York, with between 55 and 73 residents per 100,000 people. On the other end of the spectrum, Alaska, Wyoming and Idaho round out the bottom half of the list with about five to seven residents per 100,000 people. The majority of surgical programs were based in the university or university-affiliated setting (80%), according to the American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database.

What more should we know? Between these organizations, there is a treasure trove of information regarding residents and their respective programs across the United States. These entities are in a tremendous position to understand and govern change in surgical education at a national level. This approach allows for the combination of both top-down and bottom-up reconstruction and reframing of surgical education. These data can be augmented further by national resident participation.

Imagine if we asked every surgical trainee: What is the most important change to your residency program and/or hospital system to improve resident satisfaction? What other changes do you propose?

What if these responses were interpreted in the context of demographics, learning style, personality traits, geography and practice setting? Many of these data have already been collected. The responses from a national needs assessment would be immense and powerful.

For proof of concept, I attempted to informally ask these questions within my own program. Overall, my intern colleagues were most concerned about call and workroom spaces, whereas my junior and chief resident colleagues cited working with other hospital services and financial considerations, respectively. The results were simple and predictable, yet validating. Interns spend the most time taking care of patients and using hospital spaces. Junior residents work the most closely with the emergency department and other medical services. Chief residents, who are looking to graduate or move on to fellowship, invariably recognize the financial burden of medical school debt, inability to effectively invest, and various age-appropriate financial concerns, such as child care or mortgage payments. Independent of this assessment, our hospital recently improved work spaces and raised resident salaries. As for the emergency department, some things may never change.

The availability of such data on a national level would be the first, crucial step to improving resident satisfaction within postgraduate surgical education. Each trainee would have a voice that can be heard on many different levels whether by age, gender, postgraduate year, region or hospital setting. Each would have a unique impact. The success of such an approach has already been demonstrated. In Hu et al, an astounding 7,409 residents were surveyed for their study, “Discrimination, Abuse, Harassment, and Burnout in Surgical Residency Training,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019;381:1741-1752). The title is self-explanatory. The results of their study have been discussed elsewhere, but unsurprisingly reveal more pessimism without recourse.

These “big data” approaches can provide the tools to develop top-down (organization-driven) and bottom-up (resident-driven) strategies. This type of survey has the opportunity to help gain insight and understanding of what residents request from their program, hospital or organization to improve their satisfaction in an evidence-based way. This method implicitly assesses the etiology of their dissatisfaction but is not the focus. The emphasis is placed on solutions, offered by the trainees who have the most to gain at the program, regional or national level. For example, residents who are married with children may be more likely to cite a need for improved day care programs as a wellness intervention. Alternatively, residents with strong neurotic personality traits may cite access to mental health services or a need for protected time off for personal, health care maintenance or academic purposes. Residents in urban-based programs may cite transportation needs, and so on. This would be further extended to a program director’s perspective when evaluating his or her own institution: “My program is composed of 50% married residents with neurotic traits in an urban academic hospital environment, so we should review day care, mental health and transportation policies.”

We are all ultimately strangers in some way to the same surgical community—strangers who are consistently reevaluating their place in a community that is actively changing to the demands of medicine in the 21st century and internally, within the dynamic landscape of generations of surgeons simultaneously coming of age, maturing and retiring. Every five years, the demographic and associated challenges of a residency program change. The data to help anticipate and address these challenges are available, yet hidden from the community with the most to gain or lose in the next five years.