Your patient’s estimated risk for colorectal cancer could depend on which assessment tool you choose.

A new study of risk calculators found that the assessments consistently included information about age, sex, body mass index, tobacco use and family history of CRC. They were less consistent about race, education, personal medical history, diet, exercise, and use of alcohol and medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, oral contraceptives, estrogen, vitamin D and calcium.

“Given the variation in risk calculators, it is important to understand which ones are best built in terms of study population, methods used for model development, model metrics, and perhaps most importantly, the extent of testing and validation,” Thomas Imperiale, MD, the Lawrence Lumeng Professor of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the University of Indiana, in Indianapolis, and the senior author of the study, said. “It’s about knowing which one is best for your patient, your setting and so forth.”

In the study, which Dr. Imperiale and his colleagues submitted to the 2020 Digestive Disease Week, the researchers examined five online risk assessment tools for CRC to see how they compared, and whether the 3% risk threshold that has been recently recommended could apply to other models.

The researchers used scenarios for low-, average- and high-risk patients to look for variation, and they found it, according to Jennifer Maratt, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine, who helped conduct the study (abstract Tu1802).

A 15-year CRC risk greater than 3% was the screening threshold recommended by an expert panel using the QCancer risk model (Br Med J 2019;367:15515).

Models for CRC lacked consistency in the risk factors they included and the time frames across which they estimated risk. Some models predicted lifetime risk, and in these models the lifetime risk also varied, regardless of sex and race.

Variation increased for older adults and for longer time frames of estimated risk.

“It’s hard to say which calculator to use, but by taking multiple risk factors into consideration, we can start to personalize CRC screening decisions. However, if we apply a risk threshold to decide who to offer screening to, there needs to be more consistency in predicted risk and more data to show which models are the most robust so that we can use these tools in clinical practice,” Dr. Maratt said.

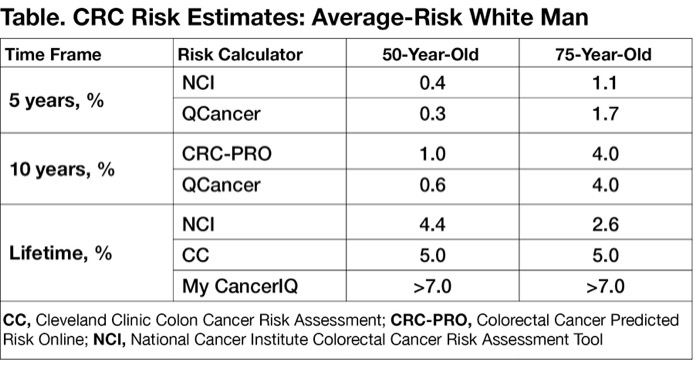

The researchers examined the National Cancer Institute’s Colorectal Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, Cleveland Clinic’s Colon Cancer Risk Assessment (CC), Colorectal Cancer Predicted Risk Online (CRC-PRO), QCancer and My CancerIQ. They looked at the factors that each tool included and assessed each’s output for three hypothetical screening scenarios, varying them by age (50 vs. 75 years), sex and race.

“Not all models provide lifetime risk estimates, but of those that do, we found more inconsistencies in lifetime estimates in comparison to shorter time frames,” Dr. Maratt said.

As an example, inconsistencies were found in 0% of five-year and 17% of 10-year time frames, but jumped to 71% of lifetime CRC risk estimate comparisons (P<0.001), according to the researchers (Table). By age, risk estimates were inconsistent for 17% of theoretical 50-year-olds, rising to 42% for 75-year-olds (P=0.02).

Only QCancer provided 15-year risk estimates. The highest screening thresholds achieved in 50-year-olds were 3.3% for white men and 2.5% for Black men. On the other hand, all sexes and races in the 75-year-old group exceeded 3%, the highest being a 17.1% risk for white men followed by 13.1% risk for Black men.

| Table. CRC Risk Estimates: Average-Risk White Man | |||

| Time Frame | Risk Calculator | 50-Year-Old | 75-Year-Old |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 years, % | NCI | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| QCancer | 0.3 | 1.7 | |

| 10 years, % | CRC-PRO | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| QCancer | 0.6 | 4.0 | |

| Lifetime, % | NCI | 4.4 | 2.6 |

| CC | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| My CancerIQ | >7.0 | >7.0 | |

| CC, Cleveland Clinic Colon Cancer Risk Assessment; CRC-PRO, Colorectal Cancer Predicted Risk Online; NCI, National Cancer Institute Colorectal Cancer Risk Assessment Tool | |||

None Ready for Routine Use

Dr. Maratt said more studies are needed to determine the internal validity of the CRC risk calculators to identify the most robust models with reliable risk estimates, “so that they can be reliably used to guide decision making.”

Dr. Imperiale said he does not use any of these models “routinely” or “quantitatively,” but based on their particular variables he may recommend one or another to a given patient. He and several colleagues developed and published a scoring index themselves for average-risk patients (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:339-356). He tends to use this “short model” or the National Cancer Institute tool, he said.

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, the GI section chief at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System, and a professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, in Minneapolis, said she would welcome an accurate CRC risk calculator, but to date, there is none.

Although risk calculators are widely used in many areas of medicine, they are challenging to develop, requiring “multiple layers of external validation in diverse populations and regular updates,” Dr. Shaukat said.

“For CRC risk, while there are several models developed, none are ready for clinical use. This is because, other than age and sex, there are not very many strong risk factors known, and their level of magnitude for risk of CRC varies,” Dr. Shaukat said. “However, the need for a risk calculator continues to grow, particularly in the COVID era, as we try to understand how to prioritize screening.”