When used appropriately, antibiotics decrease surgical site infections, mortality and cost while improving patient outcomes. When used inappropriately, they can increase infection risk, resistant pathogens, adverse events and mortality.

It’s up to surgeons to get it right, according to Addison K. May, MD, a professor and the chief of acute care surgery at Atrium Health and Carolinas Medical Center, in Charlotte, N.C.

During the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020, Dr. May shared several principles of antibiotic stewardship, which attempts to maximize the benefits of these agents while minimizing risk.

“As the patient’s surgeon, you are best positioned to influence the decisions regarding indication for antibiotic exposure and achieving adequate source control,” Dr. May said. “Decisions that you make, or at least that you influence, have very significant implications for your patient. Getting antibiotics right is your responsibility.”

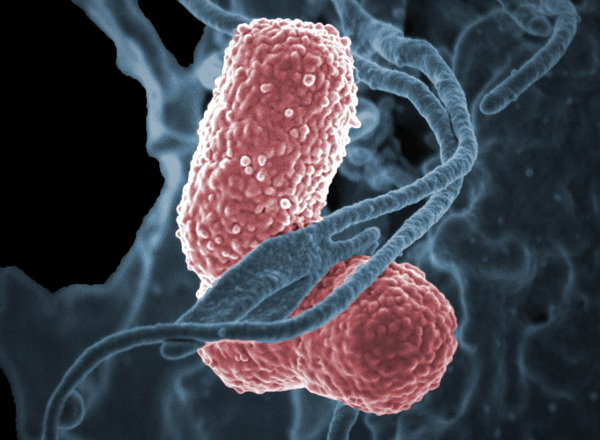

As Dr. May reported, the first death in the United States from a pan-resistant pathogen occurred in January 2017. The surgical patient, who died of sepsis from an incompletely drained seroma following a femur fracture, had been treated with multiple rounds of antibiotics and had Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated that was resistant to all 26 available antibiotics for gram-negative bacteria, including aminoglycoside and polymyxin classes. However, according to Dr. May, this complication was preventable.

Dr. May outlined six important concepts regarding antibiotic use:

Adequate spectrum of empirical antibiotic therapy and prophylaxis. Adequate empirical therapy, which is defined as covering all the involved pathogens, is strongly associated with increased survival across all sites as well as all pathogens.

Optimal timing of initial antibiotic therapy and prophylaxis. The time to initial antibiotic therapy is strongly associated with outcome, particularly for patients who are severely ill. In a study of patients with septic shock, every hour delay from hypotension to initiating antibiotics was associated with a 12% increase in the risk for death. This association is true across all pathogens and all settings.

Appropriate pharmacokinetic dosing. Appropriate dosing is required to achieve adequate levels of antibiotics at the tissue site.

Deescalation of empirical antibiotic therapy. Once the pathogen is known, deescalation of empirical antibiotics limits exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Duration of antibiotic prophylaxis and therapy. Not using antibiotics beyond their proven benefit will limit antibiotic exposure.

Avoidance of unnecessary antibiotic therapy. Use antibiotics only when you have adequate information to indicate their benefit.

“Getting the coverage and timing of antibiotic therapy right makes a big difference, but so does using antibiotics when they are not needed,” said Dr. May, who noted that excessive antibiotic use is associated with an increased risk for subsequent infectious complications in both prophylactic and therapeutic settings.

As Dr. May reported, results of a randomized trial of one versus five days of antibiotics following penetrating abdominal trauma showed that patients receiving the longer course of therapy had nearly twice the infection risk. This also holds true for other prophylactic settings in patients who are critically ill, Dr. May said, including those with head and neck cancer, pneumonia, candidemia, and extraabdominal infections when treating intraabdominal processes.

Antibiotic-Resistant Infections

Antibiotic exposure is also the single biggest risk factor for subsequent antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. This is true across all classes, Dr. May said, but is more strongly associated with some classes than others, particularly second- and third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones for gram-negative bacteria.

According to Dr. May, the risk for subsequent resistant infections increases with excessive use in both the prophylactic and therapeutic settings, and increases with each day of antibiotic exposure. A study of over 6,000 patients, for example, showed a 2.8% increased risk for antibiotic-resistant infection with each day of exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. This matters, Dr. May said, because multidrug-resistant pathogens are associated with increased mortality.

“Prolonged antibiotic therapy cannot replace source control,” Dr. May concluded. “Extending antibiotics if they haven’t worked over a short period is rarely effective over a longer period.”

Robert G. Sawyer, MD, the chair of the Department of Surgery at Western Michigan University, in Kalamazoo, noted that infection with an antibiotic-resistant organism is a product of a seriously disordered host microbiome, and exposure to antibiotics is by far the most significant event that disrupts the host microbiome.

According to Dr. Sawyer, many other risk factors for infections with resistant organisms are merely markers for possible prior antibiotic exposure, such as age, diabetes and institutionalization. Therefore, he said, the most important data to decide on altering empirical therapy are history of prior infections, colonization or antibiotic use.

“Antibiotic resistance is really, really important,” said Dr. Sawyer, who noted that appropriate empirical therapy never overrides source control. “Pervasive resistant bacteria in the community are rare, but may become more important in the United States someday.

“I usually follow guidelines, unless there is documented history of infection or colonization with a resistant organism or a recent course of antibiotics,” Dr. Sawyer added. “Act quickly when you see these patients, choose your antibiotics wisely, reassess frequently and then don’t overdo it with your antibiotics.”