From complex intraoperative decision support to the automation of robotic tasks, artificial intelligence (AI) may have the potential to forever change the face of modern surgical practice, but the road ahead is peppered with uncertainty.

In a panel session during the 2021 virtual American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress, a trio of clinicians discussed the promise and pitfalls of AI, along with its potential future directions.

In discussing the potential benefits of AI, Elsie G. Ross, MD, explained that every technology adopted in surgery has its own unique pros and cons. Nevertheless, the advancement of AI may help to address several barriers and burdens currently facing surgical practice. Dr. Ross is an assistant professor of surgery and medicine at Stanford University, in California.

Among these issues, Dr. Ross said, is the electronic health record (EHR). Developed mainly for billing, the EHR since has been adapted for other purposes, and grown exceptionally burdensome along the way. In fact, one study (J Surg Educ 2020;77[6]:e237-e244) found that surgical residents spent nearly eight months of their five-year training on the EHR.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed a set of health-system vulnerabilities that had previously gone unnoticed by many institutions. There was also a significant loss of opportunities for surgical residents to learn in the operating room. Finally, surgical practice is challenged by an ever-increasing complexity of patients and cases, in both emergent and elective circumstances.

Furthermore, although the prospect of such challenges may prove daunting to many, Dr. Ross said AI has the potential to address each one. With respect to the EHR, natural language processing (NLP) algorithms can be employed to improve the efficiency of documentation, coding and billing.

“We must completely reimagine the tedious EHR chart review, documentation and ordering process with the addition of AI,” Dr. Ross said. “Suddenly EHRs would not be so burdensome, rather could improve our productivity with automatic transcription that takes our patient visit conversations and converts them into a compliant note format.”

AI can also play a role in patient care, Dr. Ross added, particularly by transforming risk stratification into action that both improves outcomes and saves costs for healthcare institutions. Among the studies she cited, Dr. Ross discussed one (J Surg Res 2020;254:408-416), in which an AI deep learning model retrospectively identified opportunities to decrease surgical site infection rates and costs following vascular surgery, compared with a subjective practice strategy.

“Another area that AI can be of benefit is in aiding diagnosis,” Dr. Ross noted.

Research in this area has examined the potential benefits of real-time AI analysis of endoscopic images. A study (Gastrointest Endosc 2020;92[4]:905-911.e1) demonstrated the potential cost benefits of machine learning algorithms that extract polyp features and predict the likelihood of malignancies. Finally, Dr. Ross foresees a time when AI might play an important role in physician education, particularly with respect to enabling practice outside the OR.

“Regardless of all the burdens thrust upon us by our imperfect system, AI is poised to reduce administrative strains, improve patient outcomes and augment surgical training,” Dr. Ross concluded. “We have a long way to go toward developing, testing and integrating these systems into our everyday lives, but I suspect our small wins will eventually snowball into a better system in due time.”

Rachael A. Callcut, MD, MSPH, a professor of surgery at UC (University of California) Davis Health, in Sacramento, took the opposing viewpoint, choosing instead to focus on the possible pitfalls of AI in modern surgical practice.

Paramount among the problems, Dr. Callcut said, is that despite the explosion in AI-related research in surgery, only two of 2,048 articles published in 2021 were randomized controlled trials. Nevertheless, most surgeons are already using AI in their practice, although most of it goes unnoticed since it tends to deal with issues surrounding efficiencies and predictions of resource demands.

Yet despite such widespread adoption, most AI used in healthcare today is not validated and therefore potentially ignores ethnic, clinical and geographic variations.

“Most algorithms are designed and developed in very highly constrained patient data sets and patient populations,” Dr. Callcut noted. “When they’re turned into the wild, they don’t perform the way that they’re intended. It is one of the most concerning things in the field of healthcare AI right now.” Indeed, of 516 studies investigating the performance of AI algorithms for clinical use, only 6% included external validation.

Given these shortcomings, reporting standards are extremely important in AI although they are rarely followed. Whether AI is used in digital health, digital medicine or digital therapeutics, Dr. Callcut said the vast majority of algorithms do not fall under regulatory oversight. What’s more, AI algorithms have the potential to propagate biases if the data sources are biased.

Misdiagnosis is another very real potential pitfall, and one that opens the door to a host of possible legal and ethical implications. Finally, the use of AI may expose patients to several privacy concerns.

“Perception really matters,” Dr. Callcut concluded. “There have been some spectacular artificial intelligence failures outside of medicine, so we have to do this right or the public will be unwilling to accept it. Even though this is an important field with significant promise, it’s clear that we are not quite there yet.”

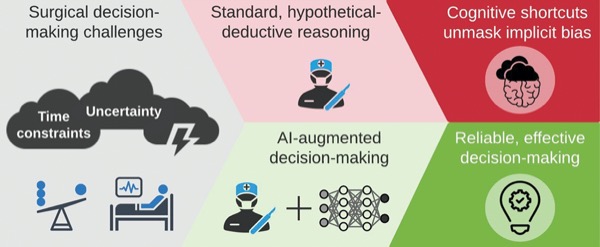

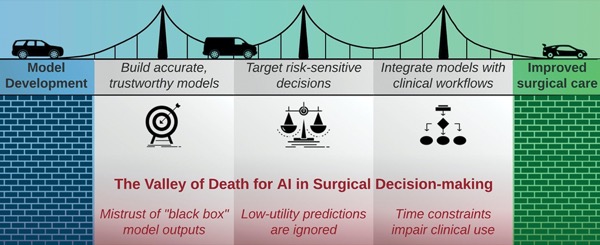

The road forward for AI was discussed by Tyler J. Loftus, MD, an assistant professor of surgery at the University of Florida, in Gainesville. As Dr. Loftus explained, the advancement of AI as a viable part of surgical practice is hampered by the substantial gap that exists between the development of AI models and the ultimate goal of clinical implementation that improves surgical care.

“This gap has been referred to as the ‘AI valley of death,’ in which AI models are hindered by a lack of transparency, physician indifference to low-utility predictions and classifications that are already addressed by standard clinical knowledge and expertise, and time constraints imposed by manual data entry requirements and lack of integration with clinical workflows,” Dr. Loftus said.

Addressing such shortcomings can be summed up in what Dr. Loftus described as the ‘desiderata’ for ideal algorithms in healthcare—a cohort of six characteristics that will make AI models more approachable in the future:

- Explainable: conveys the relative importance of features in determining outputs

- Dynamic: captures temporal changes in physiologic signals and clinical events

- Precise: data frequency matches physiology; architecture is aptly complex

- Autonomous: executes without time-consuming manual data entry

- Fair: evaluates and mitigates implicit bias and social inequity

- Reproducible: validated externally and prospectively, shared with research communities

“Current surgical care is minimally influenced by artificial intelligence,” Dr. Loftus noted. “But as artificial intelligence applications improve over time, this influence is poised to increase. Furthermore, automation of programmable tasks may allow surgeons to spend less time gathering and analyzing data, and more time interacting with patients and attending to urgent and critical aspects of patient care.

“Nevertheless, artificial intelligence is incapable of the important human traits of creativity, altruism, moral deliberation and emotional intelligence,” he added. “As such, it is unlikely that artificial intelligence will ever play a dominant role in surgical care. The surgeon’s role may evolve to interpreting artificial intelligence–enabled decision support systems and offering wisdom for patients and caregivers who are facing complex surgical decisions, as well as using semi-autonomous surgical instruments and robotic platforms in the operating room.

“Surgeons should assume active roles in guiding these technologies toward optimal patient care and net social benefit,” Dr. Loftus noted. “If we abdicate this role, then it will inevitably be performed by others.”