‘Undoubtedly, philosophers are in the right when they tell us that nothing is great or little otherwise than by comparison.’—From “Gulliver’s Travels” by Jonathan Swift

The residents’ mail was delivered halfway through morning clinic, and I opened a letter from a regional referral center in my area. I had referred a patient months ago for consideration for organ transplant, and this letter was informing me that he/she was not currently eligible but could be at some point in the future. This was a monumental decision after months of studies and appointments.

The patient I saw just before opening the letter was a routine post-op after removing some residual shrapnel debris that was causing chronic pain. The surgery had lasted all of 15 minutes, but appeared to significantly improve his symptoms. There was an irony between these two unrelated events. The letter, written on cardstock with a glossy letterhead in the left-hand corner, presented an obvious importance. Then there was the almost insignificance of removing a sub-centimeter fragment of metal from my patient. And I realized in that moment that the reason I love general surgery is because it glorifies the minutia and the hundreds of small ailments that introduce fear and pain into our patients.

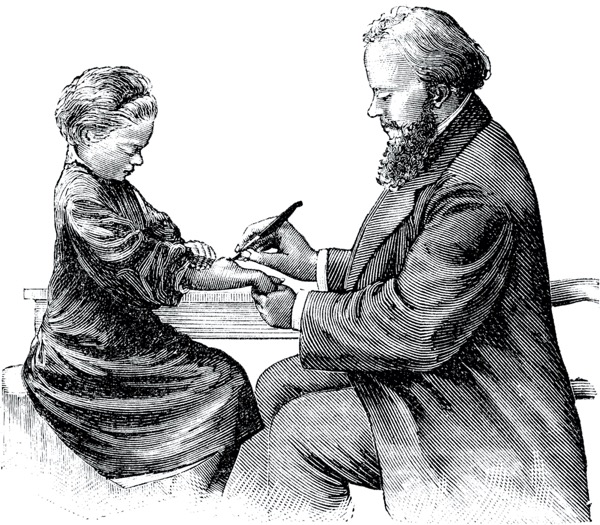

Before anything that resembled surgery today, barber-surgeons in London attempted any procedure that required a steady hand and a sharp knife. The company of men represented everything that the Royal College of Physicians looked down upon. With no formal education other than a crude apprenticeship, they were available to trim beards, bathe wounds, lance boils, pull teeth, suture and amputate. These menial public services were well beneath the physicians of the day, either thought of as too trivial or too demeaning. Now we offer complex operations, aided by technology, some that require collaboration with other services, using multiple platforms for approach. But these big moments are only possible because surgeons found significance where others found none.

Without exception, surgery residents are drawn to the big operations. To come out on the other side of a Whipple or retroperitoneal sarcoma resection feels important, and it should. I’m sure that in every training program, an inguinal hernia repair has, at some point, been labeled an “intern case;” or an upcoming adrenalectomy, a “chief case.” This kind of vocabulary is perpetuated in residency, by residents. I understand the intent behind these labels. It implies that the intern, at their current level of training, will maximally benefit from performing an inguinal hernia repair. They are, or should be, familiar with the anatomy and are technically capable of performing a lasting repair. To the latter point, the chief will benefit from reviewing the workup of an adrenal mass, should have a better grasp of the anatomy and approach, and has performed enough complex laparoscopic cases to be proficient—and not spend half the time trying to find their nondominant hand.

But these categories, I think, unintentionally embed a bias that hernias are somehow less important, or less significant, then an adrenalectomy. I want surgical interns to understand that significance is defined by the patient, and not the operation. One of my mentors told me that he receives more gifts after a lateral internal sphincterotomy than any other operation. There will never be a day when surgical interns don’t try to “out-operate” each other. But I hope the reason is because they want more complexity, more knowledge and more opportunity, and not because they are blind to the importance even a small operation can have on a patient.

Interns, go see the splinter or blister down in the emergency department when they call you. Inspect the IV the nurse just placed on your patient. Close the incision perfectly after standing for six hours with the suction. Do the small things other people don’t care to do. Find purpose in the insignificant. Because at the end of the day, there is literally nothing beneath a general surgeon.

Dr. Halgas is a chief surgical resident in El Paso, Texas. His columns on surgical residency appear every other month.

Please log in to post a comment

Excellent outlook on practice and life.

In private practice those "little things" are appreciated, and often lead to you being the one they call when bigger things in life pop up and need your help. In the Corporate Medicine World this may seem discounted - but you build a "Brand" ( how I hate that...) one brick at a time in the same way.