Originally published by our sister publication, Anesthesiology News

Reports on patient safety incidents are commonly employed to describe events that compromise safety. They are ideally used to lead to the modification of systemic factors to reduce recurrence of the event. Unfortunately, the reporter may stray from objective facts toward opinions, assumptions and accusations while completing these narrative reports. If blame is attributed in a safety report, it can muddle a clear description of an event and potentially impede the subsequent investigation.

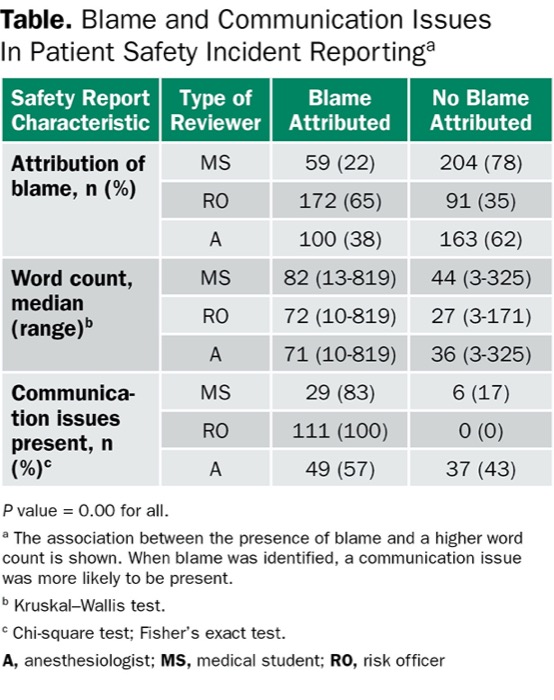

In this study, the authors sought to determine if a relationship existed between the length of the narrative in safety reports and the presence of blame. The authors hypothesized longer narratives would contain more subjective information and be more likely to attribute blame. A requirement for written informed consent was waived by the institutional review board at the University of South Florida.

Methods

All safety reports related to anesthesia services over a four-year period at a single center were retrieved and assigned to three independent reviewers: a board-certified anesthesiologist (A), a hospital chief risk officer (RO) and a medical student (MS).

Safety reports were submitted by clinical faculty and staff using a web-based, commercially available risk management software tool featuring a narrative free-text section, without specific instructions. Each reviewer independently evaluated the narrative of each report and made two determinations: whether blame was attributed to a person or entity and whether an issue with communication was reported. Blame was defined in the report by Cooper et al, as “evidence in the free-text of a judgment about a deficiency or fault by a person or people.”1 Whether or not a communication issue was present was based on the raters’ interpretation of the narrative. No additional guidance or training was provided. Yes/no determinations were made by each reviewer on the presence of blame or a communication issue. A word count was done for all safety reports.

The association between blame attribution and presence of communication issues was investigated using the chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test with continuity correction. The distribution of word count across instances with blame and without blame among all raters was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Inter-rater agreement for blame attribution was calculated using the Cohen’s weighted kappa and 95% confidence intervals.2,3

Results

This analysis was conducted on 263 safety reports related to anesthesia services. The number of reports in which blame was perceived varied significantly depending on the background of the reviewer (MS, 59; A, 100; RO, 172). The number of reports in which a communication issue was perceived also varied significantly (MS, 36; A, 86; RO, 111). The inter-rater agreement for the blame attribution and presence of communication issues was weak. However, each of the three reviewers found that both a higher word count and a communication issue were more likely to be present in the safety reports that had attribution of blame (Table). The median word count in reports including attribution of blame was 71 (MS), 72 (A) and 82 (RO) for the three reviewers. For reports without blame attributed, the median word count was 27 (MS), 36 (A) and 44 (RO).

| Table. Blame and Communication Issues In Patient Safety Incident Reportinga | |||

| Safety Report Characteristic | Type of Reviewer | Blame Attributed | No Blame Attributed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attribution of blame, n (%) | MS | 59 (22) | 204 (78) |

| RO | 172 (65) | 91 (35) | |

| A | 100 (38) | 163 (62) | |

| Word count, median (range)b | MS | 82 (13-819) | 44 (3-325) |

| RO | 72 (10-819) | 27 (3-171) | |

| A | 71 (10-819) | 36 (3-325) | |

| Communication issues present, n (%)c | MS | 29 (83) | 6 (17) |

| RO | 111 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| A | 49 (57) | 37 (43) | |

| P value = 0.00 for all. a The association between the presence of blame and a higher word count is shown. When blame was identified, a communication issue was more likely to be present. b Kruskal–Wallis test. c Chi-square test; Fisher’s exact test. A, anesthesiologist; MS, medical student; RO, risk officer | |||

Discussion

Safety reporting in health care traces its history back to aviation.4 In contrast to aviation, health care workers often do not report adverse events. A significant impediment to voluntary reporting is the punishment meted out for making an error, leading health care workers to report only what they cannot conceal.5,6 Blaming is prevalent throughout health care around the world.7,8 When an adverse event happens, it is common to point fingers at others, especially when the stakes are high.9 When completing reports that are designed to capture adverse events, it can be assumed that blame would appear, something that has likely been observed much more frequently than has been publicized.1 Despite the major drawbacks of safety reporting, it remains an important component of patient safety improvement.10,11

In our study, there was weak inter-rater agreement regardless of whether a common definition was used by the reviewers (determining the presence of blame) or not (determining the presence of a communication issue). A “subjective filter” exists for blame in all people, and perhaps the use of a common definition may not be able to override this.9 This filter could be caused by differing professional backgrounds, training, and prior experiences and exposures to the events described in the reports. Although the lack of inter-rater agreement can be seen as a limitation of this study, it reflects the heterogeneity of expertise and experience in clinical practice. Not everyone who is charged with reviewing and acting on the information contained in safety reports has the same background, training or ability to separate emotions from facts.

It is especially important to consider that the perception of blame in safety reports is not without consequence. In a study by Fausey et al, linguistics researchers had two groups of individuals view a videotape of an incident and then read different narratives of the watched event.12 Despite both groups watching the same video, the group reading a narrative with canonical agentive language (e.g., “he ripped the costume”) was more likely to attribute blame than the group that read a narrative containing canonical nonagentive language (e.g., “the costume ripped”). Typically, the reviewer of a safety report did not witness the event and therefore will form impressions only from reading the report. Bias has the potential to affect further investigation of the event.

Although the subjective determination of blame varied significantly among the reviewers, interestingly two relationships were observed: an association between the attribution of blame in the narrative and its length, and an association between the attribution of blame and the presence of communication issues. It is telling that these general associations were consistent for each reviewer, despite the weak agreement between reviewers for the reports.

Several strategies can be considered to address the presence of blame in safety reports. One tactic is to put a word limit on the narratives. The rationale for this is that the report is meant to gather facts and serve only as a trigger for “collective inquiry and coordinated action.” The investigation, conceptualization and generation of corrective actions are more important than the safety report itself.10 Fewer words may force the reporter to choose their words more wisely when completing the narrative. However, this restriction may lead to the loss of important or interesting information.4

Alternatively, safety reporting can provide instructions to describe only the facts of the case. This approach may not be consistently successful. Another approach is to focus on the reviewer rather than the submitter of the safety report. It cannot be assumed regardless of training or position that a person has the competence to review safety reports and conduct investigations. Formal instruction needs to be provided to those who review safety reports. This includes training on identifying bias in reporting, reminding those individuals that the narrative is one person’s view of a complex situation.10

These strategies may improve the quality of safety reports or decrease the bias of the reviewers, but they do not change the most important finding of our study. The significant presence of blame found in our safety reports and those in Cooper et al, indicate that much work remains to be done in transforming patient safety culture from one that focuses on blaming individuals to one that addresses the systemic issues that shaped the individuals’ behaviors.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Cohen is the corresponding author and can be contacted at Jonathan.Cohen@moffitt.org or on Twitter at @JonathanCohenMD.

References

- Cooper J, Edwards A, Williams H, et al. Nature of blame in patient safety incident reports: mixed method analysis of a national database. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):455-461.

- Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull. 1968;70(4):213-220.

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

- Cook R, Woods D, Miller C. “A tale of two stories: contrasting views of patient safety.” Presented at: National Health Care Safety Council of the National Patient Safety Foundation at the American Medical Association; January 1998; Chicago, IL.

- Brborovic O, Brborovic H, Nola IA, et al. Culture of blame—an ongoing burden for doctors and patient safety. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4826.

- Leape L. VHA’s risk management policy and performance. Presented at: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Health of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs House of Representatives; October 8, 1997; Washington, DC. Accessed October 17, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-105hhrg46316/pdf/CHRG-105hhrg46316.pdf

- Khatri N, Brown GD, Hicks LL. From a blame culture to a just culture in health care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2009;34(4):312-322.

- Parker J, Davies B. No blame no gain? from a no blame culture to a responsibility culture in medicine.J Appl Philos. 2020;37(4):646-660.

- Dattner B. Credit and Blame at Work: How Better Assessment Can Improve Individual, Team and Organizational Success. Simon and Schuster; 2011.

- Macrae C. The problem with incident reporting. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(20):71-75.

- Shojania K. The frustrating case of incident-reporting systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(6):400-402.

- Fausey CM, Boroditsky L. Subtle linguistic cues influence perceived blame and financial liability. Psychon Bull Rev. 2010;17(5):644-650.

Please log in to post a comment