By Caroline Helwick

For people with a family history of colorectal cancer but a negative screening colonoscopy, waiting 10 years for the next endoscopy appears safe—with a caveat, according to a study of patients in the Polish Colorectal Cancer Screening Program.

“Our results suggest that a colonoscopy screening interval for individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer could be safely set at 10 years, providing that the quality of baseline colonoscopy [with negative findings] is high,” Nastazja D. Pilonis, MD, of Maria Sklodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Center and Institute of Oncology in Warsaw, said. Dr. Pilonis and her colleagues submitted their findings to the 2020 Digestive Disease Week (abstract 1129).

Throughout the 10-year interval that followed a high-quality negative colonoscopy, the risk for CRC and death from the malignancy among individuals with a family history was not significantly higher than among those without such a history, Dr. Pilonis’ group found.

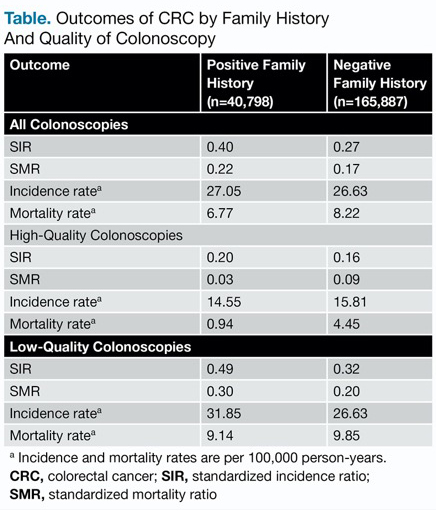

Using the general population as the reference, the standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) and standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) for the two cohorts were nearly identical. In the setting of a low-quality exam, however, family history did matter, as higher SIRs were observed (0.49 vs. 0.32), the researchers reported.

According to Dr. Pilonis, no single screening schedule has been firmly established for people with a family history of CRC. Most gastroenterologists, therefore, take a cautious approach to caring for these individuals.

“Despite limited evidence, the majority of guidelines recommend repeating screening colonoscopy in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer every five years,” Dr. Pilonis said.

With this study, she and her colleagues looked for evidence to support this practice but did not find it.

At the 2019 DDW meeting, her group reported that the risk for CRC is low for most people undergoing screening colonoscopy 15 years after a negative high-quality exam (abstract 571). Their new study looked at the long-term risk for CRC and CRC mortality within the cohort of subjects with at least one first-degree relative with the disease.

Among the 206,685 people with a negative screening result, 40,798 had a positive family history. These individuals were followed for CRC and CRC death through the National Cancer Registry over a median of 10 years.

High-quality colonoscopy was defined as an examination with cecal intubation and adequate bowel preparation, performed by an endoscopist with an adenoma detection rate of at least 20%. SIRs and SMRs were calculated by comparing the observed values with those for the general Polish population.

Throughout the 10-year period of observation, individuals with a family history who underwent screening were at 60% lower risk for CRC and 78% lower risk for CRC death than the general population (Table).

| Table. Outcomes of CRC by Family History And Quality of Colonoscopy | ||

| Outcome | Positive Family History (n=40,798) | Negative Family History (n=165,887) |

|---|---|---|

| All Colonoscopies | ||

| SIR | 0.40 | 0.27 |

| SMR | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| Incidence ratea | 27.05 | 26.63 |

| Mortality ratea | 6.77 | 8.22 |

| High-Quality Colonoscopies | ||

| SIR | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| SMR | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Incidence ratea | 14.55 | 15.81 |

| Mortality ratea | 0.94 | 4.45 |

| Low-Quality Colonoscopies | ||

| SIR | 0.49 | 0.32 |

| SMR | 0.30 | 0.20 |

| Incidence ratea | 31.85 | 26.63 |

| Mortality ratea | 9.14 | 9.85 |

a Incidence and mortality rates are per 100,000 person-years. CRC, colorectal cancer; SIR, standardized incidence ratio; SMR, standardized mortality ratio | ||

The importance of a high-quality examination was clear. Within the family history cohort, a high-quality exam was associated with more than a halving in the risk for CRC and CRC death compared with low-quality exams, Dr. Pilonis reported.

‘Not All Family History Is Equal’

C. Richard Boland, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, said the observations are important because most guidelines recommend surveillance colonoscopy every five years in the setting of a positive family history, rather than every 10 years as for the general population aged 50 years and older.

“The study’s results should be put into the calculus of determining optimal and most cost-effective approaches to CRC screening as these guidelines are revisited,” Dr. Boland said. A more detailed assessment of family history would help refine the risk.

Most CRCs are sporadic, but those associated with family history or genetic syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome, often are complex entities for which surveillance strategies should be nuanced. In 1995, Vasen et al, from the Netherlands, found that interval cancers may still occur in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis CRC—at the time, defined as having three or more affected family members across two generations—undergoing colonoscopy every two to three years (Lancet 1995;345[8958]:1183-1184). Later, in a 2010 study, Vasen et al examined the Dutch Lynch syndrome registry of “high-risk” patients with a positive family history (Gastroenterology 2010;138[7]:2300-2306).

Using a screening interval of one to two years versus a longer period, the risk for CRC among family members was reduced. However, the risk remained significantly higher in the Lynch syndrome cohort than the group without the syndrome. The authors concluded that based on this low risk, people with a positive family history but not Lynch syndrome could undergo “a less intensive surveillance protocol.”

“Not all high-risk family histories are equal,” Dr. Boland concluded, “which points the way to more individualized ‘precision’ prevention strategies.”

Dr. Boland reported consulting to and serving on the speakers bureau of Ambry Genetics. Dr. Pilonis reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Please log in to post a comment